CASANOVA 1725-2025:

L’eredità di un mito tra storia, arte e cinema

29 August – 2 November 2025

Venice, Museo di Palazzo Mocenigo

Curated by

Gianni De Luigi

Monica Viero

Luigi Zanini

![]()

Exhibition itinerary

Giacomo Casanova

A lively biography

Very few historical figures can boast of being known in every corner of the planet and of having become an icon over time: to be a Casanova still means today to be an unrepentant seducer, a hardened libertine, an unscrupulous adventurer.

Very few historical figures can boast of being known in every corner of the planet and of having become an icon over time: to be a Casanova still means today to be an unrepentant seducer, a hardened libertine, an unscrupulous adventurer.

Here, then, is how his myth, which already developed during his lifetime and was fervently sustained in the centuires that followed, would go on to distort his memory and obscure a balanced, accurate account of the events of his life. Casanova himself was complicit in this, through the stories he told in his Mémoires.

He was born in Venice in 1725, possibly the illegitimate son of the nobleman Michele Grimani and an actress. After graduating in law from the University of Padua, he soon embarked on a life that was adventurous to say the least. Of libertarian ideas and a member of the Freemasons, intellectually and emotionally restless, his reputation even made him suspicious in the eyes of the State Inquisitors of Venice, so much so that he was imprisoned in the Piombi prison, where in 1756 he was the protagonist of the famous night-time escape, perhaps partly romanticised but certainly described and celebrated by himself. From that moment began his long and eventful European exile.

His return to Venice in 1774 found him in such financial straits that he had to find a stable source of income, perhaps for the first time in his life. The now mature Casanova chose the path of literature, but not before unsuccessfully attempting to become a ‘confidant’, or spy, for the very same State Inquisitors who had imprisoned him years earlier.

His most famous works date from this period, and include his translation of the Iliad and the pamphlets collected in the Opuscoli Miscellanei, an encyclopaedic work on a wide variety of subjects. Published in only seven monthly instalments, this work bears testimony to Casanova’s profound and vast culture, and includes short stories, epistolary novels, articles of opinion, political and autobiographical essays.

He even reinvented himself as a theatre impresario, attempting to establish a Comédie Française theatre in Venice. He hosted the first performances at the Teatro di S. Angelo and promoted the initiative by publishing a weekly magazine in French, Le Messager de Thalie, which served to present the programme.

The initiative was not successful due to poor audience response, while the publication of his last satirical text, Né amori né donne, ovvero La stalla ripulita, in which he used mythology to ridicule a member of the noble Venetian Grimani family over an unpleasant financial matter, caused a great stir and resulted in his having to embark on his final exile.

By now advanced in years and disillusioned, in 1785 he accepted a position as librarian at the castle of Dux – now Duchhov – in Bohemia, in the service of the Count of Waldstein. Here, in order to survive a sad and – for someone so thirsty for experience – sterile isolation, he devoted himself to frequent correspondence with friends and confidants and to writing Jcosameron, a melancholic but witty utopian novel.

But the real antidote to the boredom and sadness of his declining years was the compilation of his monumental Memoirs. In Histoire de ma vie, he recounts all the events of his extraordinary life from birth to 1774, probably reluctant to narrate the last sad decades of his existence, which was cut short by his death in 1798.

A painting and a poster

Two portraits compared

The painting on display here depicts an elegant and refined eighteenth-century gentleman dressed in the fashion of the time, with adornments and accessories identical to those in the portrait of the Count of Colloredo, also by Longhi.

The gentleman is holding a small bound book in his right hand and next to him, resting on a table, are three other volumes.

The resemblance to portraits of Giacomo Casanova, particularly the one attributed to Anton Raphael Mengs from 1767, would seem to confirm the identity of the famous Venetian.

The portrait can be dated thanks to the style of the elegant velada (tailcoat) and camisiola (waistcoat or undercoat), which are coordinated in fabric and silver embroidery and correspond to the fashion of the period when Casanova travelled to Russia (1765), invited to the court of Catherine II.

The subject’s stance is the result of a graceful yet studied pose, as is the position of his left hand and certain gallant details that signal refinement and distinction.

These include the ring on the little finger of his right hand, a diamond set in a gold mount, and his hairstyle, powdered with what is almost certainly perfumed powder.

His neck is encircled by a solitaire, a black ribbon used to hold back a ponytail or wig, contrasting with the snow-white lace ruffles that barely peek out from the neckline of his waistcoat, falling limply and abundantly onto his wrists.

The film poster, on the other hand, introduces a different figure, where the image of Giacomo Casanova is reinterpreted under the artificial light of the spotlights. After reading Casanova’s Memoirs, Fellini developed a deep and unshakable aversion towards him: he said that he was not an artist and that he had only written a kind of telephone directory.

He interpreted him as an accountant, a bookkeeper, a provincial playboy who believed he had lived but had never even been born. A figure who travelled the world without ever existing, who went through life like a wandering ghost.

He hated this empty character, a prisoner of his own obsession with sex and appearances, and so he made a film about existential emptiness, about a fellow who never stopped acting and forgot to live his life.

In the end, Fellini’s Casanova, having become a puppet himself, mechanically fixates on the hopeless contemplation of his female universe.

For the director, he is also a symbol of the artist trapped in the neurotic dimension of creative illusion, which he recognised as the cause of the hostility he aroused.

The actor Donald Sutherland, chosen by Fellini for the lead role, broke drastically with the classic and heroic representation of the seducer par excellence, proposing instead a cold, mechanical, almost dehumanised Casanova, an automaton driven by desire and emptiness.

The actor’s face was carefully shaped using a wig, pale greasepaint and prosthetic make-up, making the only thing that remained real all the more poignant: his gaze.

Between dream and camera

A biography of Federico Fellini

Federico Fellini (Rimini, 20 January 1920 – Rome, 31 October 1993) was one of the greatest directors and screenwriters in the history of cinema. His work had a profound impact on Italian and international cinema, thanks to his unmistakable style that blended dreams, memories, satire and magical realism.

From a young age, Fellini showed an interest in drawing and comic writing. He moved to Rome in 1939 and began working as a cartoonist and radio writer. During the 1940s, he entered the world of cinema as a screenwriter, working for directors such as Roberto Rossellini and contributing to the famous Roma città aperta (Rome, Open City, 1945).

He made his directorial debut in 1950 with Luci del varietà (Variety Lights), co-directed with Alberto Lattuada. His first personal success came with Lo sceicco bianco (The White Sheik, 1952) and, above all, with I vitelloni (1953), a bitter yet affectionate tale of provincial stagnation. True international recognition came with La strada (1954), winner of the Oscar for Best Foreign Language Film. This was followed by masterpieces such as Il bidone (1955) and Le notti di Cabiria (Nights of Cabiria, 1957), both marked by a strong humanistic and symbolic imprint.

In 1960, Fellini revolutionised the language of cinema with La dolce vita, a monumental work reflecting on the crisis of modern man. The film sparked scandal and controversy, but won the Palme d’Or at Cannes. With 8½ (1963), Fellini reached the peak of his creativity: a meta-cinematic work that explores identity and art, still considered one of the pinnacles of world cinema.

In the years that followed, Fellini continued to experiment: Giulietta degli spiriti (Juliet of the Spirits, 1965), Fellini Satyricon (1969), Roma (1972) and Amarcord (1973, his second Oscar) paint the picture of a dreamlike, surreal, grotesque and often autobiographical world. The circus, the Italian provinces, childhood, memory and the unconscious became recurring elements in his poetic universe.

In the 1980s and 1990s, he continued to make films such as E la nave va (And the Ship Sails On, 1983), Ginger e Fred (Ginger and Fred, 1986) and La voce della luna (The Voice of the Moon, 1990), maintaining his visionary style, even if less in the public eye.

Fellini received five Oscars (four for foreign films and one for his career in 1993), the Palme d’Or, the Golden Lion for Lifetime Achievement and numerous other awards. He is considered a master of modern cinema, capable of transforming emotions, dreams and reality into unforgettable images.

He died in Rome on 31 October 1993, one day after his 50th wedding anniversary with Giulietta Masina, his muse and leading actress in many of his works.

Fellini’s cinema is a journey into the human mind and heart, where memory blends with dream and imagination surpasses reality. His films do not aim to depict the world as it is, but as it is perceived through the lens of childhood, desire, and melancholy. Fellini transformed cinematic language into a poetic and dreamlike medium, capable of evoking deep emotion through surreal imagery, recurring symbols, and grotesque yet profoundly human characters.

Eloquent fabrics and fashions

The costumes of Fellini’s Casanova

Danilo Donati (Luzzara, 6 April 1926 – Rome, 2 December 2001) was a set designer, costume designer and writer who trained at the Art Institute of Florence and then, in the same city, at the Academy of Fine Arts in the studio of the painter Ottone Rosai. A fellow student of Franco Zeffirelli, in the post-war period he began working in the entertainment world almost by chance, first with Luchino Visconti on several operas at La Scala in Milan, then in Rome, invited by friends from his youth, first and foremost Zeffirelli. It was in 1959 that he made his debut in the field of cinema, on the set of Mario Monicelli’s La Grande Guerra (The Great War), winner of the Oscar for Best Foreign Film in 1960, the Golden Lion and countless other awards.

The six costumes on display, made by the historic Farani theatre costume workshop and now part of its archive, emphasise the coexistence, in the same film, of different worlds, the result of Fellini’s dreamlike and surreal fantasies: the scene at the Marquise d’Urfè’s house is narrated with graceful pastel taffeta, while the costumes for the sex contest in the Roman mansion, bulky and still with a baroque feel, are composed of voluptuous and grand velvets and coloured satins.

And then there is the dinner at the home of the Marquis Du Bois, where the Spanish courtiers are dressed in austere black, their mood sombre, in stark contrast to the charming members of the French court, who are captured in a varied explosion of colours, styles and finery.

Federico Fellini and Danilo Donati thus exaggerate the Rococo style’s taste for exaggeration and the grotesque, emphasising and sometimes critically transforming the already excessive fashions of the time.

The voluminous silhouettes, overflowing lace and sumptuous fabrics transform the characters into masks of desire, decadence and loneliness.

Each costume is conceived not as a mere scenic ornament, but as an outward expression of the character’s inner world. Alongside the setting, it contributes to the film’s artificial and suspended aesthetic, where the body is concealed, displayed, embalmed, and staged as a symbolic object, perfectly aligned with Fellini’s vision.

Casanova, enclosed in a cage lined with silk, seems an actor trapped in the role of the seducer, incapable of forming genuine human connections due to the lack of authenticity in his relationships. Clad in an aesthetic armour, he embodies the impossibility of love, the illusion of eroticism, and the existential void that permeates the entire film.

The choice of costumes was therefore fundamental to a psychological interpretation of the character, as Casanova himself attests in his Memoirs, describing the clothes he wore when he presented himself at the court of Naples in 1744:

“At lunch, I had the honour of sitting to the right of the duchess, who, after carefully inspecting my attire, felt compelled to remark that she had never seen anything more elegant. ‘That is precisely my intention, madame,’ I replied, ‘for this is how I seek to divert attention from a more careful examination of my person.”

Turning a film into a painting

Fellini’s sketches for Casanova

In Casanova, editing and narration take a back seat to the composition of the shot, the ‘fixed picture’ of meticulously studied and constructed images in Studio 5 at Cinecittà. The image conceived for Casanova is a closely controlled one, realising perspectives, volumes, colours and, above all, light, according to imagination and without external inconveniences. The result is a highly ‘theatrical’ film, in which both the precision in the reconstruction of the settings and meticulousness in the creation of the costumes were both entrusted to Danilo Donati, one of the great masters of Italian cinema, who had already collaborated with directors such as Monicelli, Rossellini, Pasolini, Zeffirelli and Lattuada, and who lent his ingenuity and mastery to a series of Fellini masterpieces, from Satyricon (1969) to I Clowns (1970) and Amarcord (1973).

The selection displayed here brings together and bears witness to Donati’s work for Casanova through a series of sketches of film sets and costumes from the Cirulli collection, with which Donati first imagined and then gave shape to Fellini’s dreamlike and surreal fantasies. Casanova represents the pinnacle of Donati’s work for Fellini. For this film, the Italian set designer won the 1977 Oscar for ‘Best Costume Design’ – his second, after the one for Zeffirelli’s Romeo and Juliet in 1969 – followed by two Nastri d’Argento awards in 1977 for best set design and best costumes.

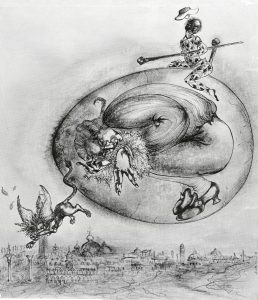

As Donati’s drawings show, the artistic style of Casanova is all about a poetic vision made up of vagueness, subtle dreamlike images, blurred fantasies, and abnormal and absurd situations and characters. Fellini’s eighteenth century is not the Age of Enlightenment, but a subterranean, sepulchral world reminiscent of certain expressions of Baroque art. Dark, nocturnal tones emblematically dominate the Venetian scenes.

For his cinema, which was more ‘painting than literature’, Fellini, together with Donati and Peppino Rotunno, director of photography, revisited the forms, lights and colours of eighteenth-century painting, from Hogarth to Gainsborough, from Watteau to Chodowiecki, from Francesco Guardi to Canaletto, but with references also to Tiepolo and the Metaphysical painting of Giorgio De Chirico.

As Donati himself explained, in keeping with Fellini’s work of fusion and stylistic hybridisation of iconographic sources, Casanova’s eighteenth century is ‘updated’ and redefined in the light of early twentieth-century ‘Venetian Art Deco’ or a metaphysical surrealism that draws on the valuable collaboration of artists such as Roland Topor, among others.

The iconographic repertoire of reference draws not only from painting, but also from opera, illustration, ballet sets, pantomimes and popular masks. This repertoire is explicitly referenced in the preparatory work, both in the screenplay published by Einaudi, and in Donati’s stage sketches.

Fellini was attracted by the ‘theatrical’ and ‘spectacular’ dimension of the Venetian man of letters. Casanova’s eighteenth century embraced a certain idea of stage and spectacle that spilled over into the Baroque but also anticipated Romanticism, with references to Verdi’s operas.

The motif of spectacle, acting and artifice dominates the film visually from the very first shots, presenting a Venice as theatre, with the Grand Canal becoming the stage for a masked ball, with hundreds of characters-spectators, music, fireworks, acrobats and a large female head, symbol of Venice, emerging from beneath the water. The theatre and sets are all interiors, counterbalanced by a nocturnal and twilit Venice.

An eighteenth-century dressing room

Paintings of mythology and licentiousness

The three paintings on display here, depicting Apollo, Venus and Diana, come from the Miari de Cumani heirs, descendants of two ancient Venetian families, which owned various palaces, villas and castles between Padua and Belluno. The most famous in Padua was the palazzo Cumani in Scalona, in Via San Gregorio Barbarigo, which housed a rich picture gallery, later dismembered and dispersed due to the vicissitudes of the family.

In 1964, Egidio Martini published the Venus and Diana paintings as works from Giambattista Pittoni’s full artistic maturity, and in 1979, Franca Zava Boccazzi included them in her monographic catalogue as mature masterpieces of the artist, postdating them to the 1730s.

However, after cleaning and their inclusion in the Steven V. Maksin Family Collection (Las Vegas, Nevada, USA), they are now backdated to the late 1720s.

The figures of Apollo, Venus, and Diana engage in a captivating interplay of sensual gazes, a game of love in which one can glimpse the presence of Giacomo Casanova himself, the undisputed protagonist of countless erotic seasons and perfectly at ease in refined and voluptuous settings such as the one evoked by these three paintings, contemporaneous with Casanova’s birth.

His sharp, mischievous gaze can be ideally traced in the eyes of Apollo, who fixes his stare on the naked forms of Diana and Venus – the former languid and drowsy, the latter alert and aware.

Pale, cheerful, and brilliantly luminous colours; smooth skin, glossy satins, bodies with elastic, undulating forms; limbs soft and graceful; flesh rosy and pulsing with feminine heat, or full and virile with youthful maturity; pupils fixed and unmoving, or eyelids closed in deep sleep – everything is rendered with the precision of a perfect Rococo ritual.

This refined and erudite painting favours virtuosic, aesthetic execution while never neglecting the erotic charge so characteristic of the Venetian Rococo – sophisticated and frivolous, yet always exquisite, delightful, charming, and filled with delicate longing.

Everything is harmony in the figures surrounded by faithful winged cherubs and a sleeping dog that amplifies the sense of abandonment of the senses. Each character is semi-nude, draped in the ancient style, in a vaguely Arcadian setting, but with a precise individual character and animated body and facial expressions.

The relationship between painting and theatre is a persistent feature of all Venetian figurative art in the early eighteenth century, present in paintings with historical and mythological subjects or ancient fables. These intentional theatrical poses of the figures, which today we might describe as almost cinematic, focus above all on the characters and their facial expressions in a ‘recitar cantando’ style with clear, spontaneous and immediate accents, elaborated in a charming and persuasive manner.

The three deities probably belonged to a single setting that we could define as a boudoir, well evoked by this intimate room in the Mocenigo Palace, elegantly decorated with stuccoes in light pastel shades.

Aldo Ravà and the eighteenth century

An apologia for Casanova

It was only in the early twentieth century that a substantial group of scholars began to rediscover and promote the lesser-known aspects of Giacomo Casanova, in an effort to rehabilitate his image as a true witness of his time. Until then, he had been associated almost exclusively with the reputation – already earned during his lifetime – of an unrepentant libertine, swindler, adventurer, and spy. Aldo Ravà (Venice, 1879–1923) soon became one of the most prominent figures of this new and compelling line of scholarship. His important archive of work and his rich library are now preserved at the Correr Museum Library. Born in Venice into one of the city’s wealthiest Jewish families, he devoted himself to historical and artistic studies and collecting. His early cultural interests are evidenced by his numerous connections with the cultured Venetian milieu and its institutions, as attested by his membership cards on display.

In 1907 in Nice, he married Mary Violet Fenton, a refined and cultured heiress from Chicago, with whom he established an extraordinary intellectual partnership and who, after Ravà’s early death, continued his work and his activities as a collector. Palazzo Cavalli Corner Martinengo on the Grand Canal, formerly the Ravà family residence, became the couple’s home and the place where they collected and studied an extraordinary collection of books, archival documents and art objects, relating to eighteenth-century Venice. His important monographs on Pietro Longhi (1909), Giovan Battista Piazzetta (1921) and Marco Pitteri (1922) are dedicated to the protagonists of this century, without neglecting literature and theatre, with studies on Pietro Chiari and Carlo Goldoni and, of course, Giacomo Casanova.

1910 can be defined as Aldo Ravà’s Casanova year, thanks to his discovery, in the Querini Stampalia Library in Venice, of Casanova’s Opuscoli veneziani and Messanger de Thalie, which had hitherto been lost. The scholar promptly informed the Leipzig publisher Albert Brockhaus, who, wishing to publish the complete manuscript of Casanova’s Memoirs in his possession, invited Ravà to compile a biography and a complete bibliography of Casanova. There was a copious exchange of letters and postcards between the two, unfortunately interrupted by the death of Brockhaus, which also blocked the publication of the complete Memoirs, which were only published in 1960.

A large collection of postcards recounts Ravà’s journey in the summer of 1910 to Duchcov, Bohemia, to the castle where Casanova ended his days as a librarian, and to whose collections Count Waldstein gave him full access. Countless unpublished documents were unearthed here, such as those that made up Casanova’s personal library, as well as precious first editions of his works and letters from his numerous female friends and lovers, copied by Ravà to study in Venice and which, reread without preconceptions, led to the publication of Lettere di donne a Giacomo Casanova (1912).

Several articles in Il Marzocco testify to an initial reorganisation of the enormous mass of documents examined; Studi casanoviani a Dux is the first of more than twenty contributions dedicated by Ravà to Casanova and his world. The materials collected enabled Ravà to publish, in 1910, a first Contributo alla bibliografia di Giacomo Casanova, followed by many other articles which, in his archive, accompany the manuscripts and preparatory materials useful for publications.

The Ravà Collection, which came into the possession of the Museo Correr in the 1960s, contains also a priceless selection of first editions of Casanova’s works; among them the exceptionally rare Jcosameron (1787) and Histoire de ma fuite (1788). Alongside these are copies of later editions, in various formats and languages, which testify to a renewed interest in the figure of Giacomo Casanova.

Learn more about the collector Aldo Ravà and his studies on Giacomo Casanova >

Admission to the exhibition with the Museum’s hours and ticket.